Hypothesis Testing

'’Hypothesis Testing’’ is a framework of testing some assumptions in Inferential Statistics

- a result is ‘‘statistically significant’’ if it’s very unlikely to have happened due to chance alone

Motivation

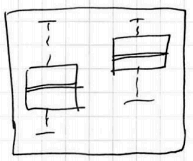

Suppose we have 2 groups and we observe the difference between them

<img src=” ” />

” />

Question:

- Is this difference significant?

- Could the difference be due to natural variability of the Sampling Distribution?

- Or we have something stronger?

'’Statistical tests’’ (often as well called “Hypothesis tests” or “Tests of Significance”) answer these questions.

Structure of Statistical Test

Summary

- Determine the $H_0$ and $H_A$

- Collect data and calculate a ‘‘test statistic’’

- Calculate the $p$-value

- Make a conclusion based on it and on the context

Step 1: Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Formulate a hypothesis what you want to test and specify its alternative

Court case analogy: Innocent until proven guilty

- “Innocent” part

- null-Hypothesis $H_0$ (read as “H-naught”)

- it’s a skeptical position or position of no difference

- example: no relationships, no difference, etc

- we assume it’s true

- “Guilty” part:

- alternative hypothesis $H_A$ (or $H_a$ or $H_1$)

- it’s a new perspective

- this is what a researcher wants to establish

- example: relationship, change, difference

And we question we ask is do we have enough evidence to rule out any difference from the $H_0$ that are just due to chance?

Like in a court, we conclude that $H_A$ is true if we have evidence against $H_0$.

Alternatives could be

- one-sided (greater than or less than)

- two-sided (not equal)

So the first step is

- ’'’clearly specify the null and alternative hypotheses’’’

Step 2: Evidence - Test Statistics

- '’The evidence’’ is provided by our data

- We need to summarize the data into a ‘‘test statistics’’: a numerical summary of the data.

A test statistic is made under assumption that $H_0$ is true

So the 2nd step is

- ’'’Collect the data and calculate a test statistic assuming $H_0$ is true’’’

Step 3: $P$-value

- Is the evidence (the test statistics) good enough to reject the $H_0$?

’‘$p$-value’’

- helps us to answer this question: it transforms the test statistic into a probabilistic scale:

- it’s a number between 0 and 1 that quantifiers the strength of evidence against the $H_0$

- formally, $p$-value is a conditional probability of

- observing data favorable to $H_A$ and to the current data set

- given $H_0$ is true

It answers the following question

- Assuming $H_0$ is true, how likely it is to observe a test statistic of this magnitude just by chance?

- And the numerical answer is the $p$-value

The smaller the $p$-value the stronger the evidence against $H_0$

| ’'’Note | ’’’ | - $p$-value cannot be interpreted as how likely it is that the $H_0$ is true. | - $p$-value tells you how unlikely the observed value of the test statistics (and more extreme value) is if the $H_0$ was true. |

So the 3rd step is

- ’'’determine how unlikely the test statistic is if the $H_0$ is true’’’ (or, calculate the $p$-value)

Step 4: Verdict

Based on the $p$-value make a verdict:

- $p$-value is not small

- $\Rightarrow$ conclude that the data is consistent with the $H_0$

- $p$-value is small

- $\Rightarrow$ then we have sufficient evidence against $H_0$ to reject it in favor of $H_A$

- we say “we fail to reject $H_0$”

Strength of the evidence:

- $p < 0.001$ - very strong

- $0.001 \leqslant p < 0.01$ - strong

- $0.01 \leqslant p < 0.05$ - moderate

- $0.05 \leqslant p < 0.1$ - weak

- $p \geqslant 0.1$ - no evidence

The result is statistically significant if the evidence is strong.

The final step:

- ’'’make a conclusion based on the $p$-value’’’ and on the context of the problem (important| ) | |

Common Test Statistics

- $z$-tests - normal, for comparing means

- Binomial Proportion Tests - for comparing proportions, typically approximated by $z$ statistics as well

- $t$-tests - like $z$, but more relaxed (uses $t$-distribution, for comparing means

- $\chi^2$-tests - for normality, variance and goodness of fit

- $F$-tests (ANOVA) - for checking more than 2 samples for equality of means

Terms

- Critical Value

- Power of a test

- Significance level

- $p$-value

- Type I and II Errors (“Decision Errors”)

Decision Errors

| + Summary [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Type_I_and_type_II_errors] || | $H_0$ is true | $H_0$ is false | Reject $H_0$ | align=”center”| Type I error

False positive || align=”center”| Correct outcome

True positive || Fail to reject $H_0$ | align=”center”| Correct outcome

True negative || align=”center”| Type II error

False negative |

Significance Level

- The ‘‘significance level’’ of a test gives a cut-off for how small is small for a $p$-value

- It’s denoted by $\alpha$ and called “desired level of significance”

- $\alpha$ shows how the testing method would perform in repeated sampling

- If $H_0$ is true and you use $\alpha = 0.01$, and you carry out a test repeatedly, with the same size of a sample each time, you will reject $H_0$ 1% of the time, and not reject 99% of the time

- If $\alpha$ is too small, you may never reject $H_0$, even if the true value is very different from the $H_0$

Choosing $\alpha$

- traditionally, $\alpha=0.05$

- if making Type I Errors is dangerous, or especially costly, choose small $\alpha$

- in this case we want very strong evidence to support $H_A$ before rejecting $H_0$

- if Type II Errors are more costly, then take higher $\alpha$, e.g. $\alpha=0.1$

- here we’re careful about failing to reject $H_0$ when it’s false

Robustness

A statistical test is ‘‘robust’’ if the p-value is approximately correct even if some conditions aren’t fully satisfied

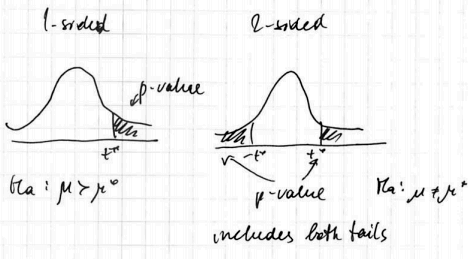

One-Sided vs Two-Sided

Alternative hypotheses $H_A$ could be one-sided or two-sided

- if it’s one-sided we look only at the corresponding tail of our Sampling Distribution

- otherwise we look at both tails

Consider the following one-sample $z$-test for means:

One-Sided

- $H_0: \mu = \mu_0, H_A: \mu > \mu_0$

- $\mu_0$ is called the “null value” because we assume it under $H_0$

- i.e. we want to check if population mean is larger than some value

- under the Normal Model we calculate the $z$-score and corresponding $p$ value of the right tail

- (source: OpenIntro, figure 4.16)

Analogously, for

- $H_0: \mu = \mu_0, H_A: \mu < \mu_0$

- we calculate the $p$-value based on the left tail

- (source: OpenIntro, figure 4.16. modified)

Two-Sided

Two-Sided alternative hypotheses looks at both left and right tails. E.g.

- $H_0: \mu = \mu_0, H_A: \mu \ne \mu_0$

- (source: OpenIntro, figure 4.19, modified)

- if this case, we reject $H_0$ if the test statistics gets under any of the shaded tails

- i.e. the $p$-value is (typically) twice bigger than for one-sided tests

Advice for Hypothesis Testing

$p$-values

- Don’t misinterpret $p$-values (see what p-values say and what don’t)

- A $p$-value is a measure of the strength of the evidence - so don’t forget to report it

Data Collection

Data Collection matters

- Sample wisely:

- use randomization to avoid flaws and biases

Two-Sided Tests

Always try to use 2-sided tests

- Unless you’re really sure you need one direction

- $p$-value for one-sided test is 0.5 of p-value of 2-sided

One-sided hypotheses are allowed only before seeing the data

- it’s never good to change 2-sided to 1-sided after observing the data

- it can cause twice more Type I errors (False positives - i.e. rejecting $H_0$ when it’s true)

Practical Significance

Statistical significance $\neq$ practical significance

- the larger the $n$, the smaller $p$-value

- A large $p$-value doesn’t necessarily mean that the $H_0$ is true, there might be not enough power to reject it.

Small $p$-values can occur (in order of significance:)

- '’by chance’’

- data collection is biased

- violations of the conditions

- $H_0$ is false (the last one| - so be more careful about those above!) | | So

- If multiple tests are carried out, some are likely to be significant by ‘'’chance alone’’’

- If $\alpha = 0.05$ we expect significant results 5% of the time, even when the $H_0$ is ‘'’true’’’

- $\Rightarrow$ be suspicious if you see only a few significant results when many tests have been carried out

Data Snooping

- The test results are not reliable if the statements of the hypotheses are suggested by data.

- This is called ‘‘data snooping’’ - So hypotheses should be specified before any data is collected

General Advice

- Start with Explanatory Data Analysis e.g. using Plots and Summary Statistics

- watch for skewed distributions, Outliers, etc

- before using some test statistics, make sure the corresponding assumptions about the data hold

Relationship with Confidence Intervals

Some hypothesis can be checked with Confidence Intervals

- e.g. if the null value (the value under $H_0$) is included in the CI, then $p$-value is greater than $\alpha$ and we fail to reject $H_0$

See Also

Sources

- Statistics: Making Sense of Data (coursera)

- OpenIntro Statistics (book)

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Statistical_hypothesis_testing